TL;DR

-

what this is: This is a hands-on guide where I share my 10-month path from “just a UX/UI designer with an idea” to “founder building a real product from scratch,” with AI embedded at every step.

-

who it’s for: Designers who dream of becoming founders, and anyone curious about using AI as a practical co-pilot for building digital products.

-

what you’ll learn: How to define your Big Idea, assess potential, talk to users, set up an AI-powered workflow, and create a strong product design. All based on real hands-on experience.

-

my ambitious goal: Give you a realistic playbook for turning a dream into something tangible and move beyond the pretty-but-empty Behance/Dribbble case study format we’ve all stopped trusting.

-

reading time: ~50 minutes.

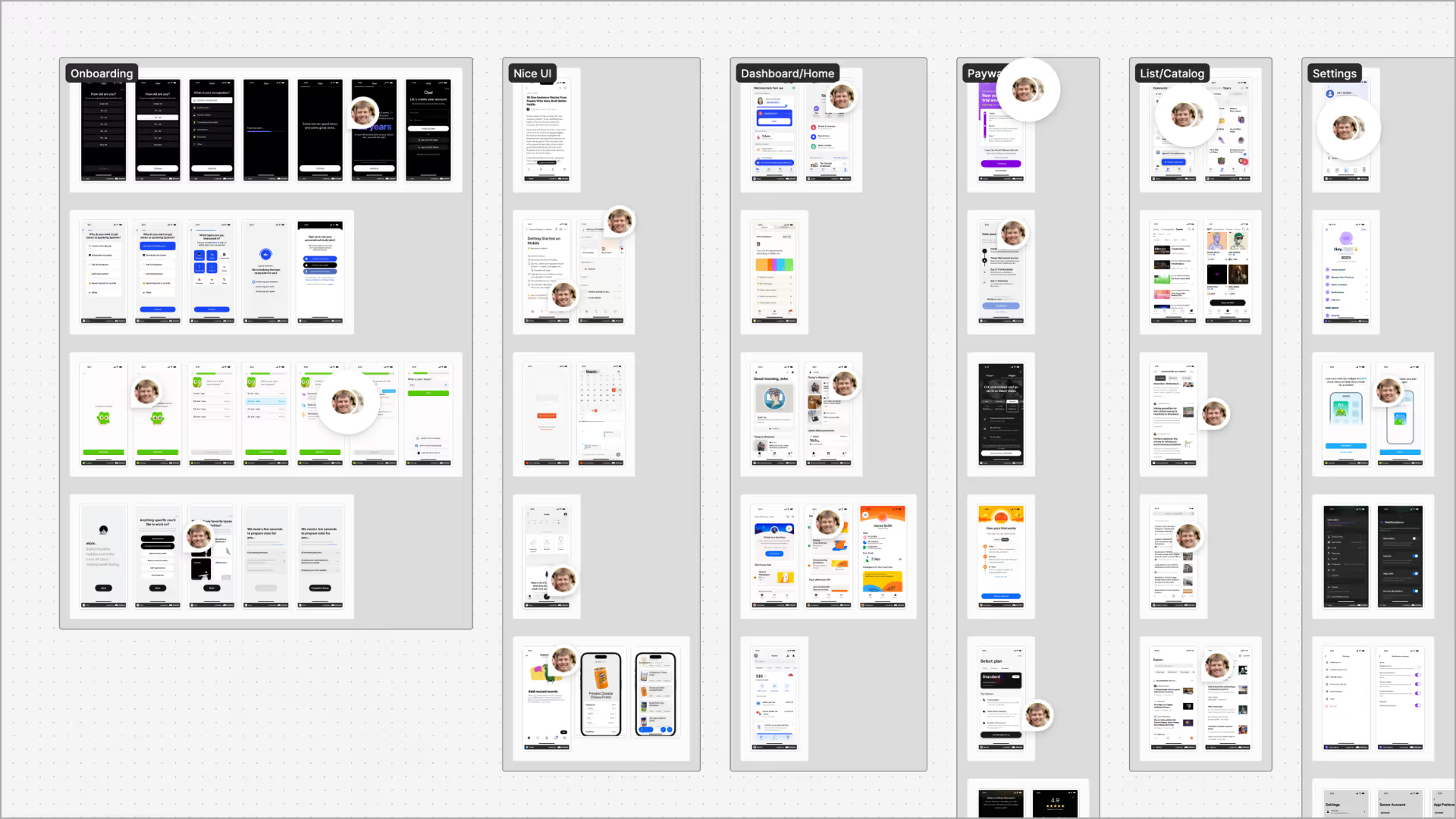

Ten months of late nights and weekends. Dozens of AI experiments. 70+ final screens (and plenty more variations). And, most importantly, a ton of valuable lessons learned.

It started last summer with a simple idea that popped into my head right before sleep. Not long after, I stumbled on a really well-timed entrepreneurship course. Back then, I had no clue how much the decision to work on a personal product would reshape my career.

I’m Volodymyr Merlenko, a product designer with four years in design and the last two deep in AI. I write articles about it, run a small LinkedIn blog, and occasionally give talks and mentoring sessions. In my free time this past year, I’ve also been building a product to help tech folks finally master the skills they keep putting off “for later,” and do it in a way that’s easy and personalized.

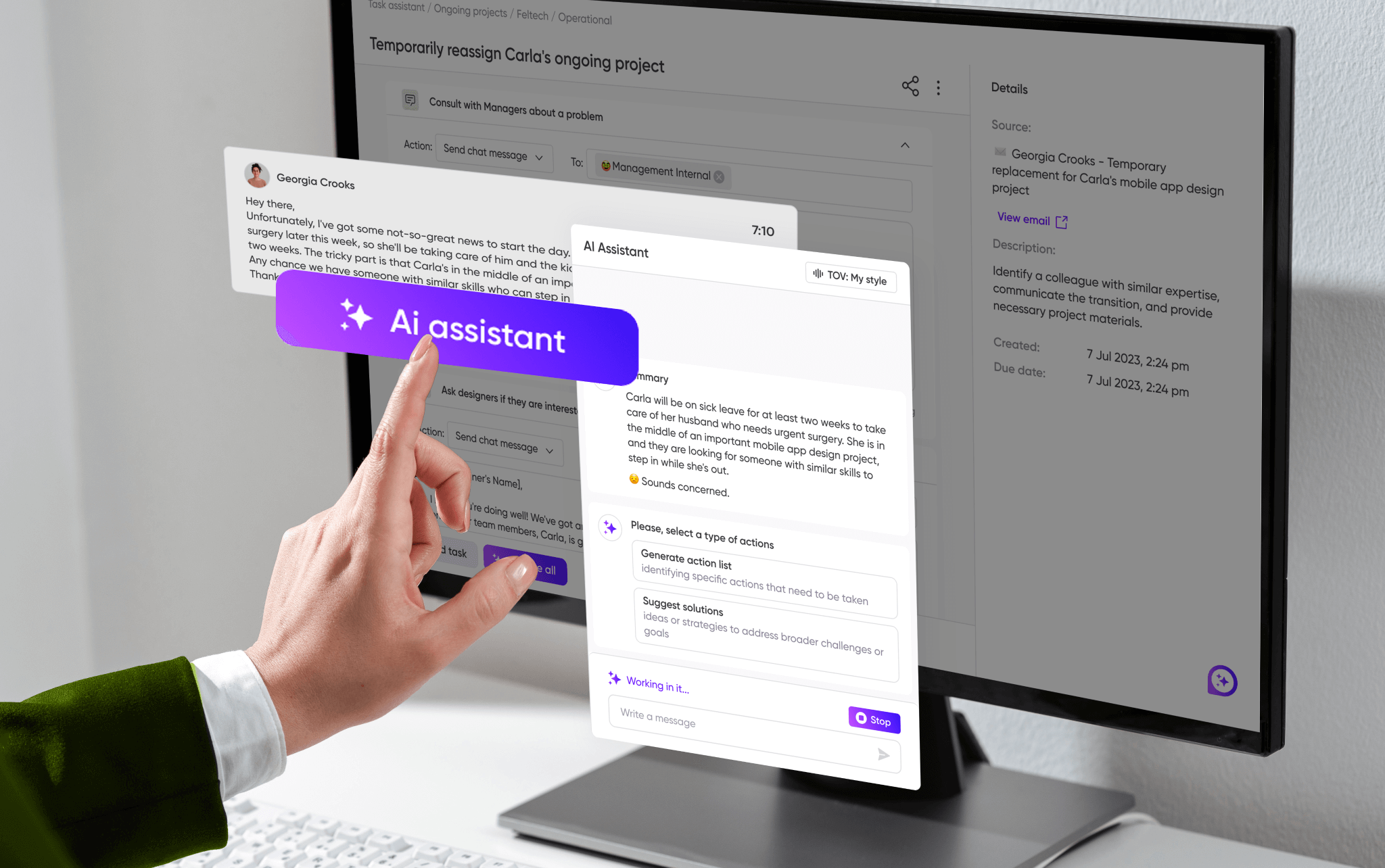

The old way most teams work? Endless calls you didn’t need to attend, messy comms, slow-motion bureaucracy, and hours lost on low-impact tasks.

The new way? A single designer, supercharged by AI, doing the work that used to take a small team.

This article is Part 1 of that journey: how I’m building a real product from zero and how AI upgrades every step.

So grab a coffee, block out an hour in your calendar, and let’s go. ☕️

Big Idea

Every product starts with a spark. But before you rush into wireframes or mockups, you need something simple to guide you – a Big Idea doc. It does two things really well:

1. Checks whether your idea solves a real problem for a real person.

2. Highlights risks before you spend time and money.

It doesn’t need to be perfect or polished; it just needs to make sense to you and your future users.

What I usually include:

-

problem statement: What real issue exists out there, and why current solutions don’t cut it;

-

user persona: Who struggles the most with this problem, and what their day-to-day looks like;

-

assumptions & hypotheses: Your best guesses, phrased so they can be tested later;

-

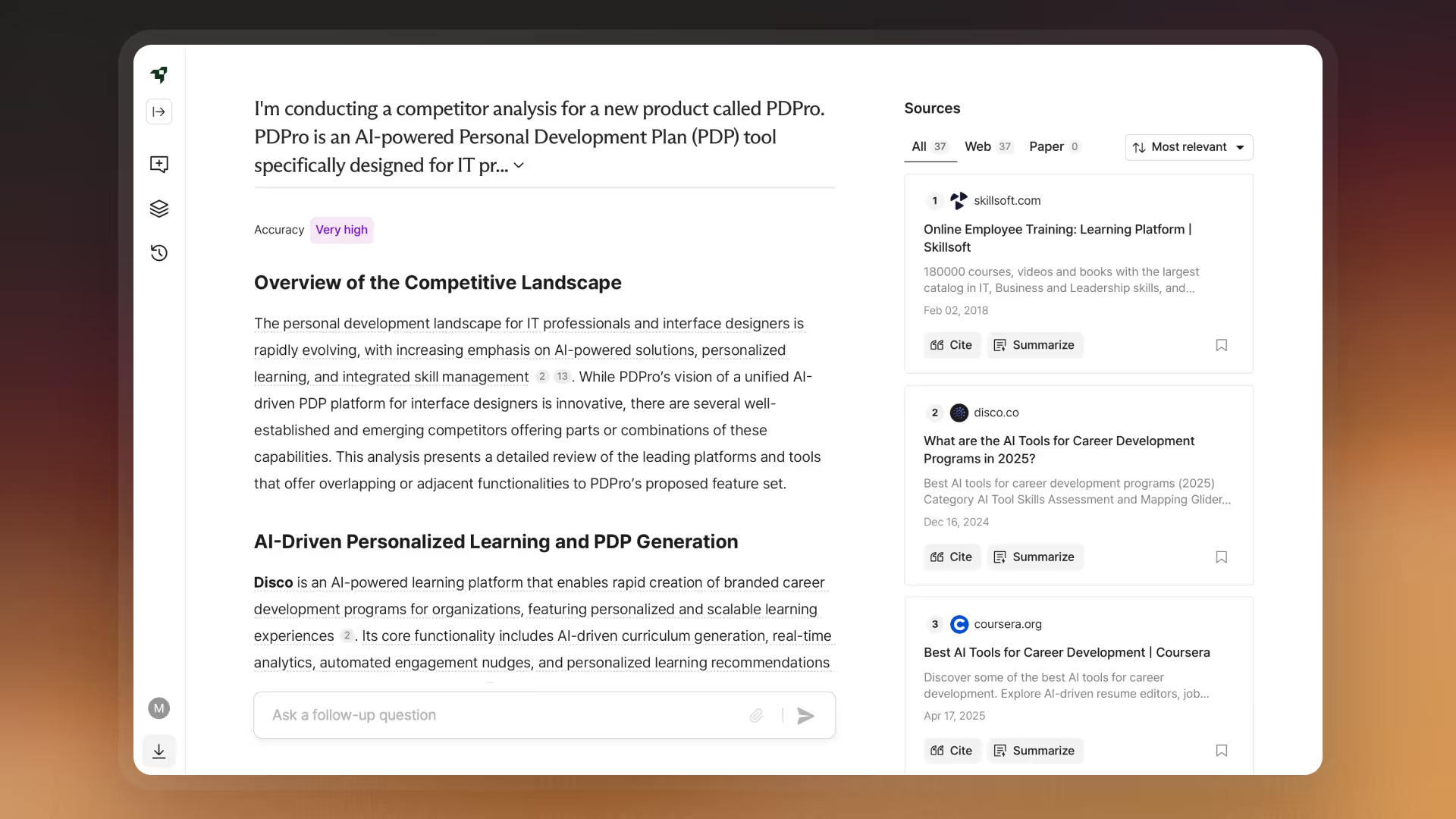

competitive analysis: How others are approaching it (direct and indirect competitors);

-

business plan: The basic mechanics of how this thing could make money;

-

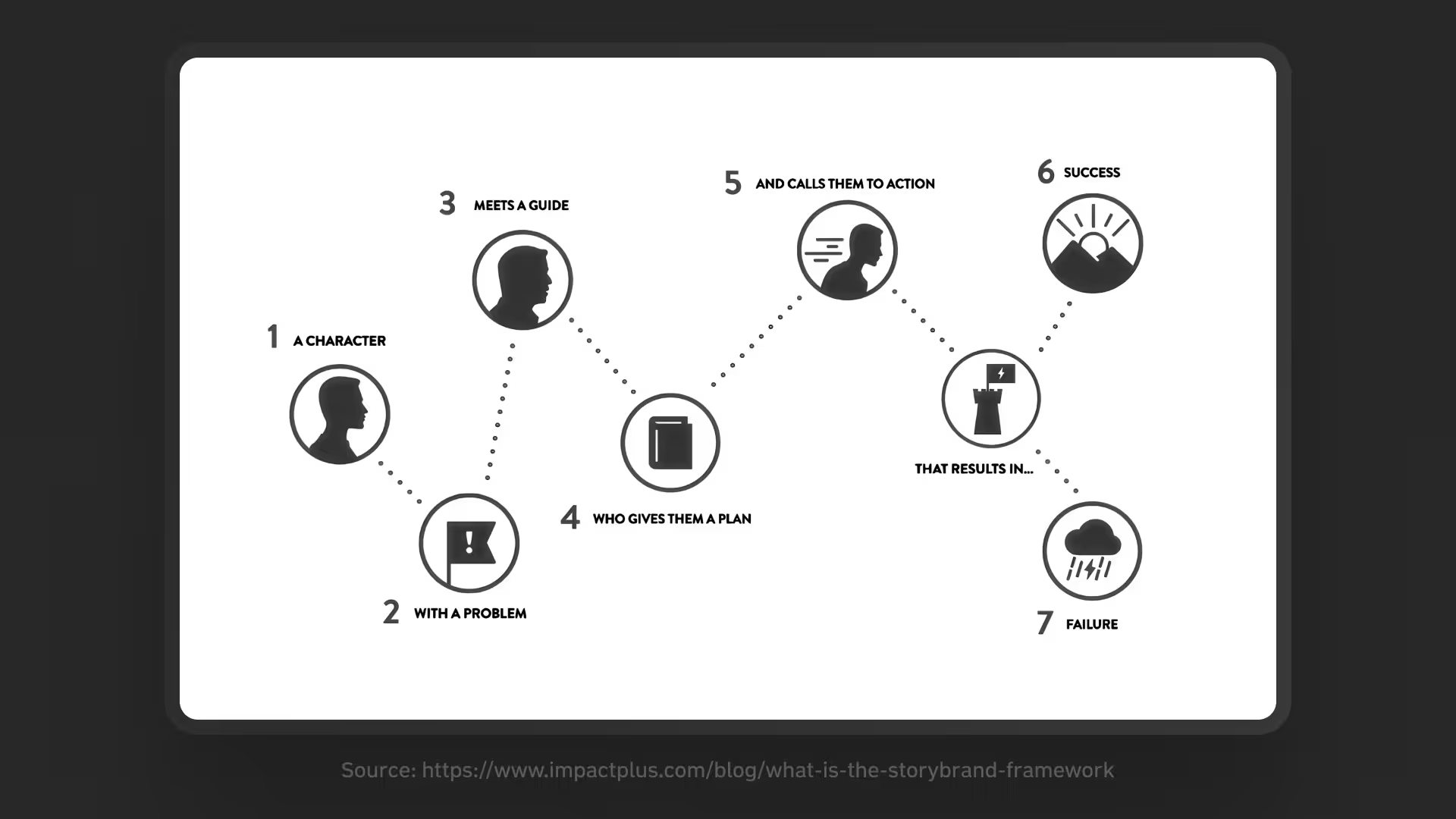

StoryBrand framework: The narrative that makes the user the hero, not the product;

-

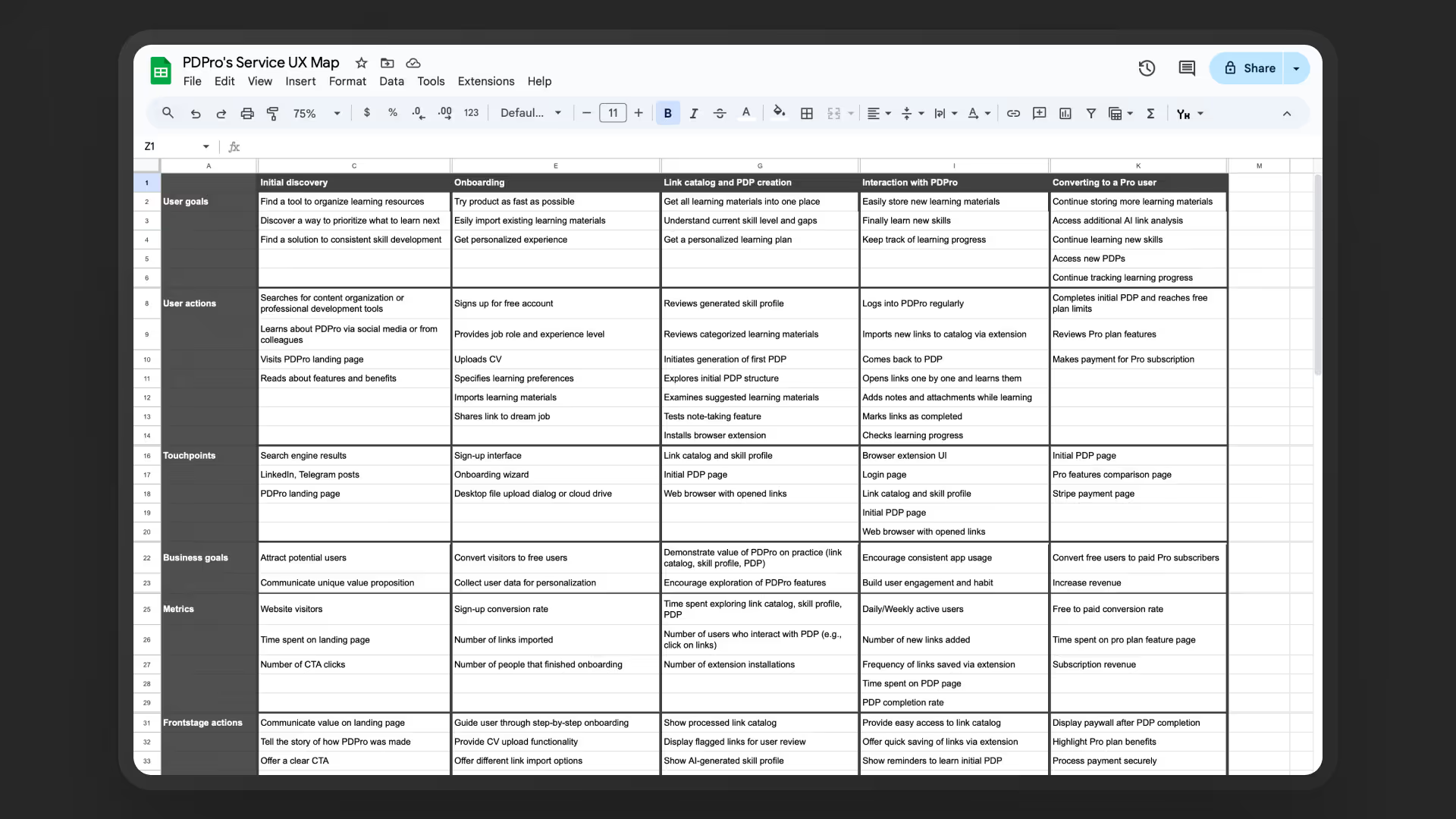

service UX map: A mix of CJM and Blueprint to see both user and system sides of the journey;

-

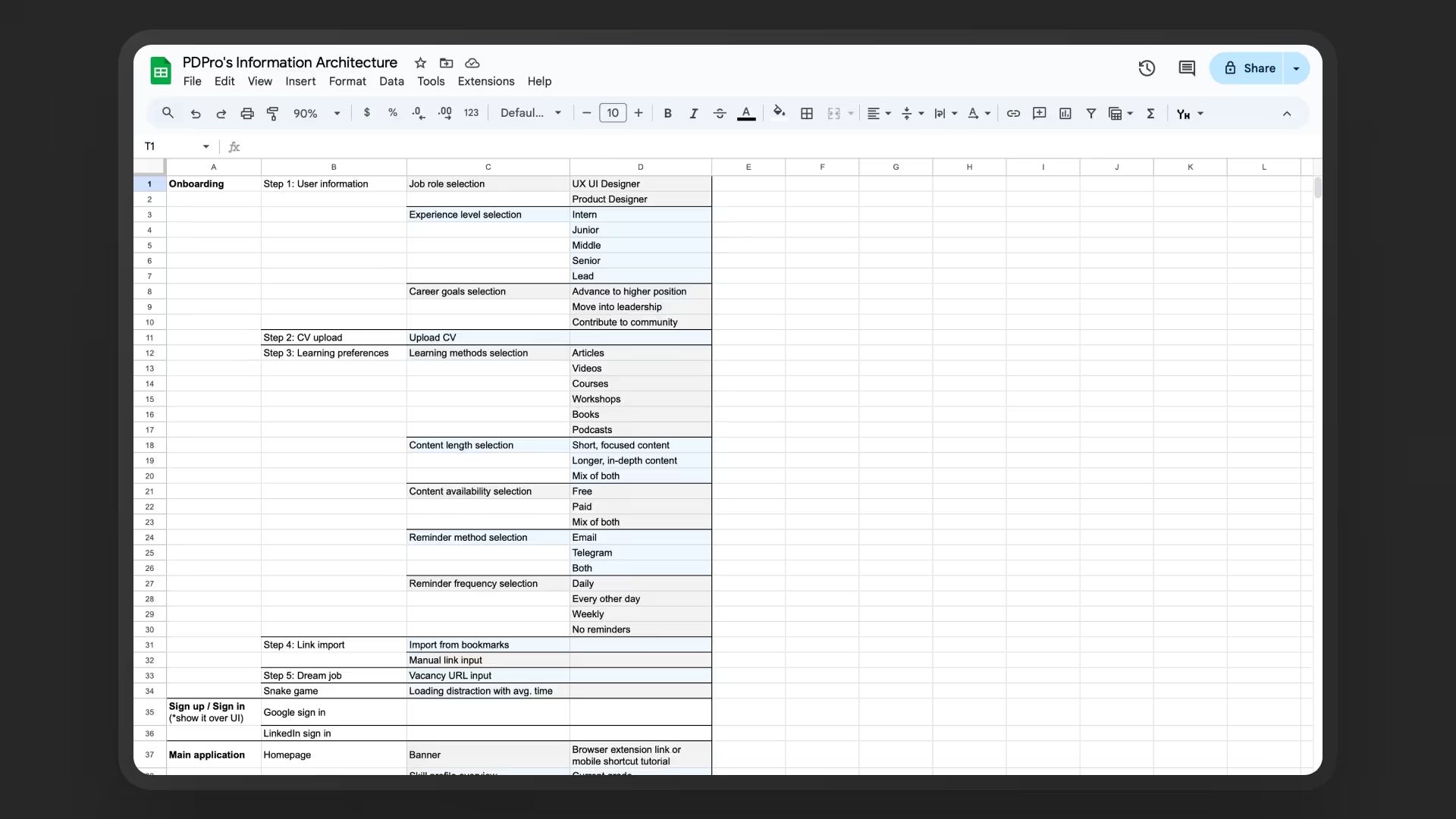

information architecture: The first sketch of how everything fits together;

-

MVP requirements: The smallest version that actually delivers value;

-

parking lot: A backlog for ideas that sound cool but don’t belong in the first release.

💡Two important reminders:

-

1. Don’t expect version 1 to be “the final one.” Mine usually evolves 10+ times as I run interviews and tests. That’s a good sign and means you’re learning.

-

2. Be ready to kill your darling. If the idea doesn’t solve a real problem or looks like a financial black hole, it’s better to pivot now than a year in.

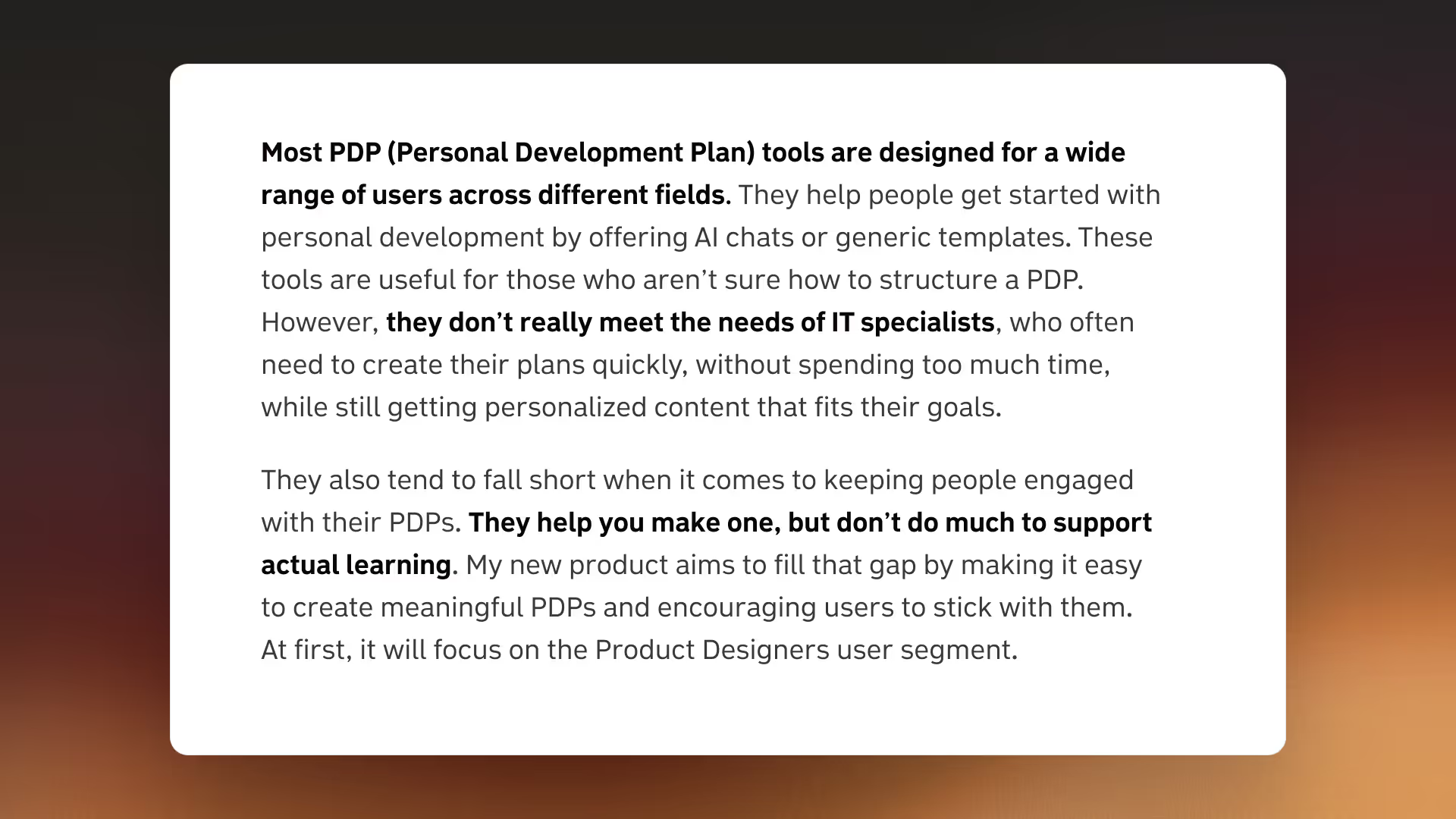

Define you problem statement

The very first step in building a product is defining the problem you’re solving. Without this, everything else (personas, hypotheses, even design decisions) will float in the air without a foundation.

A solid problem statement answers three key questions:

-

what problem exists right now that isn’t being solved well?

-

who feels this pain the most?

-

how will your product make their life better?

Keep it short and concrete. Don’t describe features or solutions yet, just stay focused on the pain.

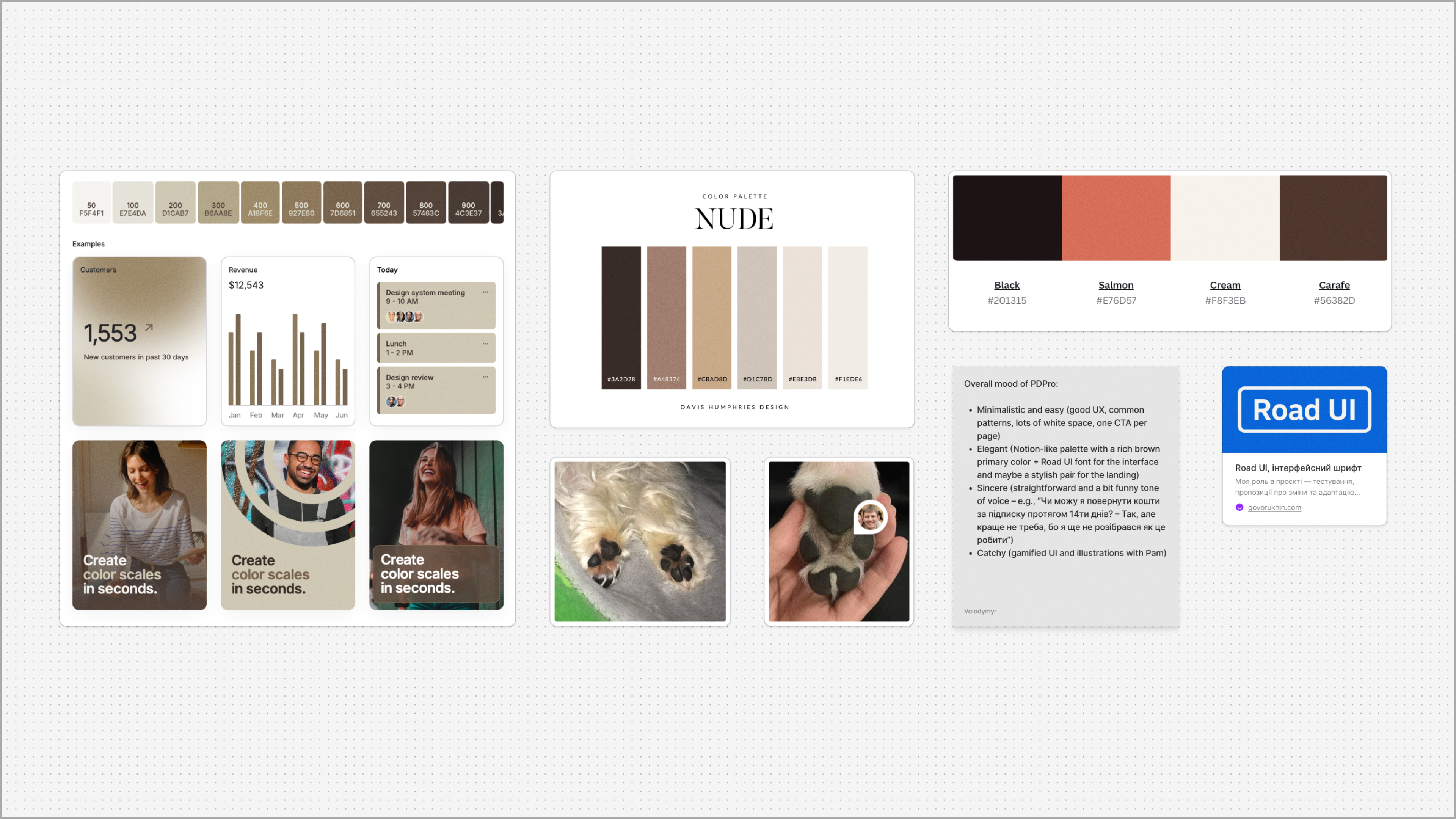

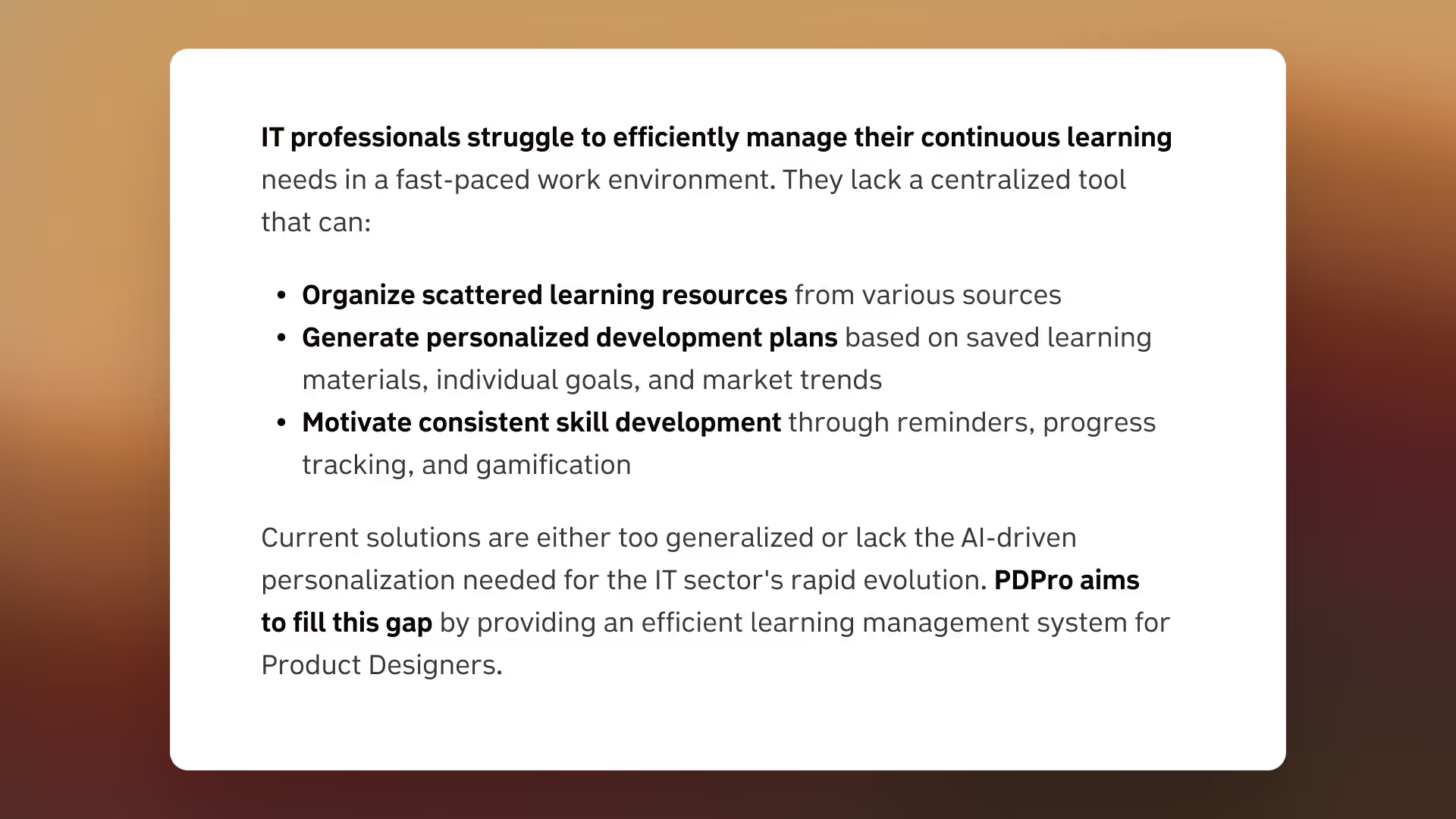

When I started working on PDPro, here’s how my initial draft looked:

At first glance, it seems okay. But in reality, it was already slipping into “solution mode” (motivation, personalization). The stronger version came later:

Create your user persona

A user persona helps you stay focused on who you’re building the product for. Every time a new idea pops into your head, check it against the persona. This way, you avoid one of the most common traps – building features instead of solving real needs.

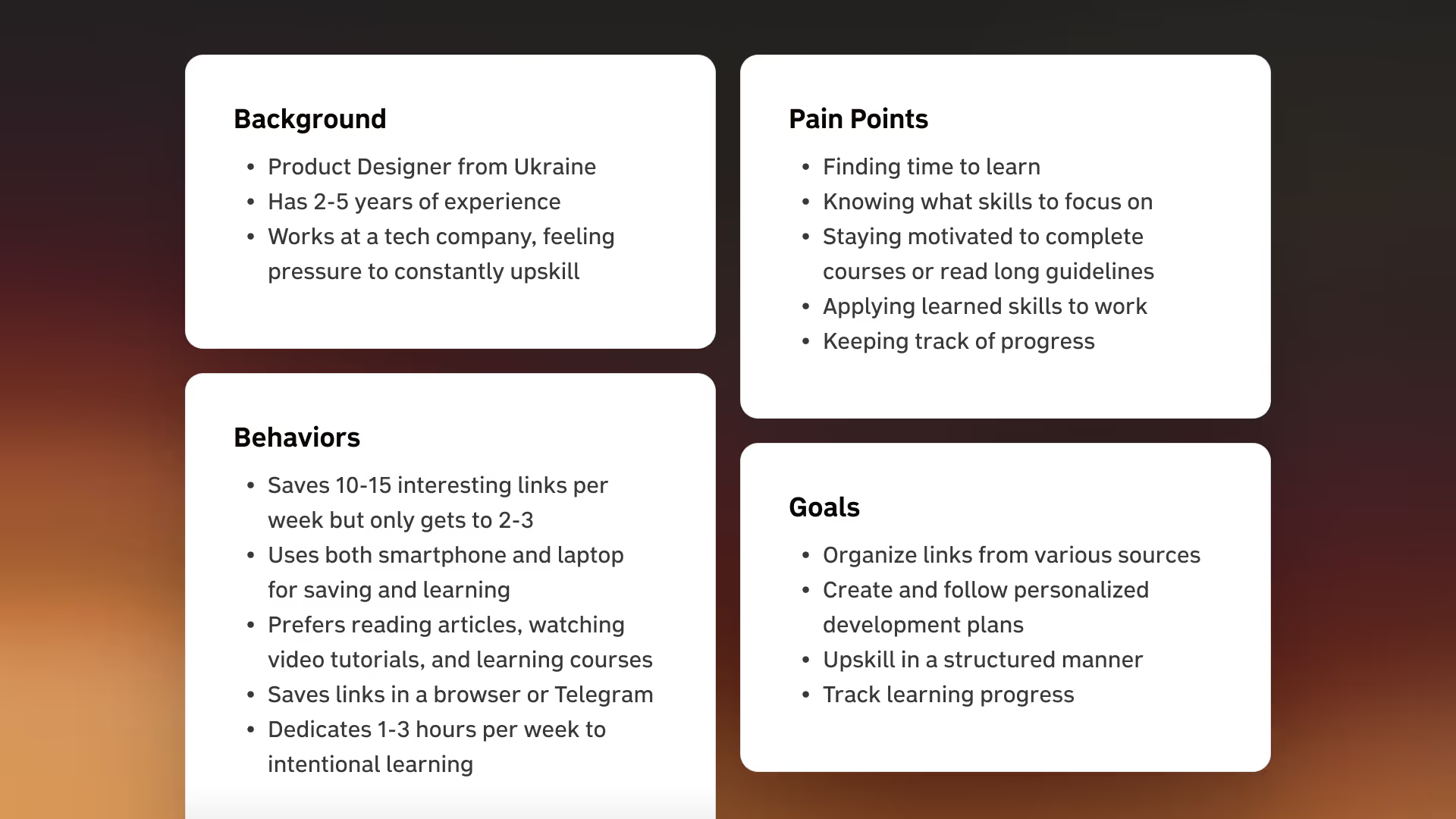

You can start with a proto-persona: basically, your best guess of who the user is, even without solid data to back it up. Later, you’ll refine it as you gather insights from surveys and user tests.

There’s no universal template for a persona, and the details will always depend on your product. Still, I recommend focusing on four categories:

-

background: Their role, environment, and daily situation;

-

behaviors: How they act, make decisions, or approach the problem area;

-

pain points: What frustrates them most about today’s solutions;

-

goals: What “better” looks like for them.

Let me give you a quick example:

Write your assumptions and hypotheses

There are two main types of hypotheses:

-

those based on user, product, or business assumptions;

-

and those tied to functionality.

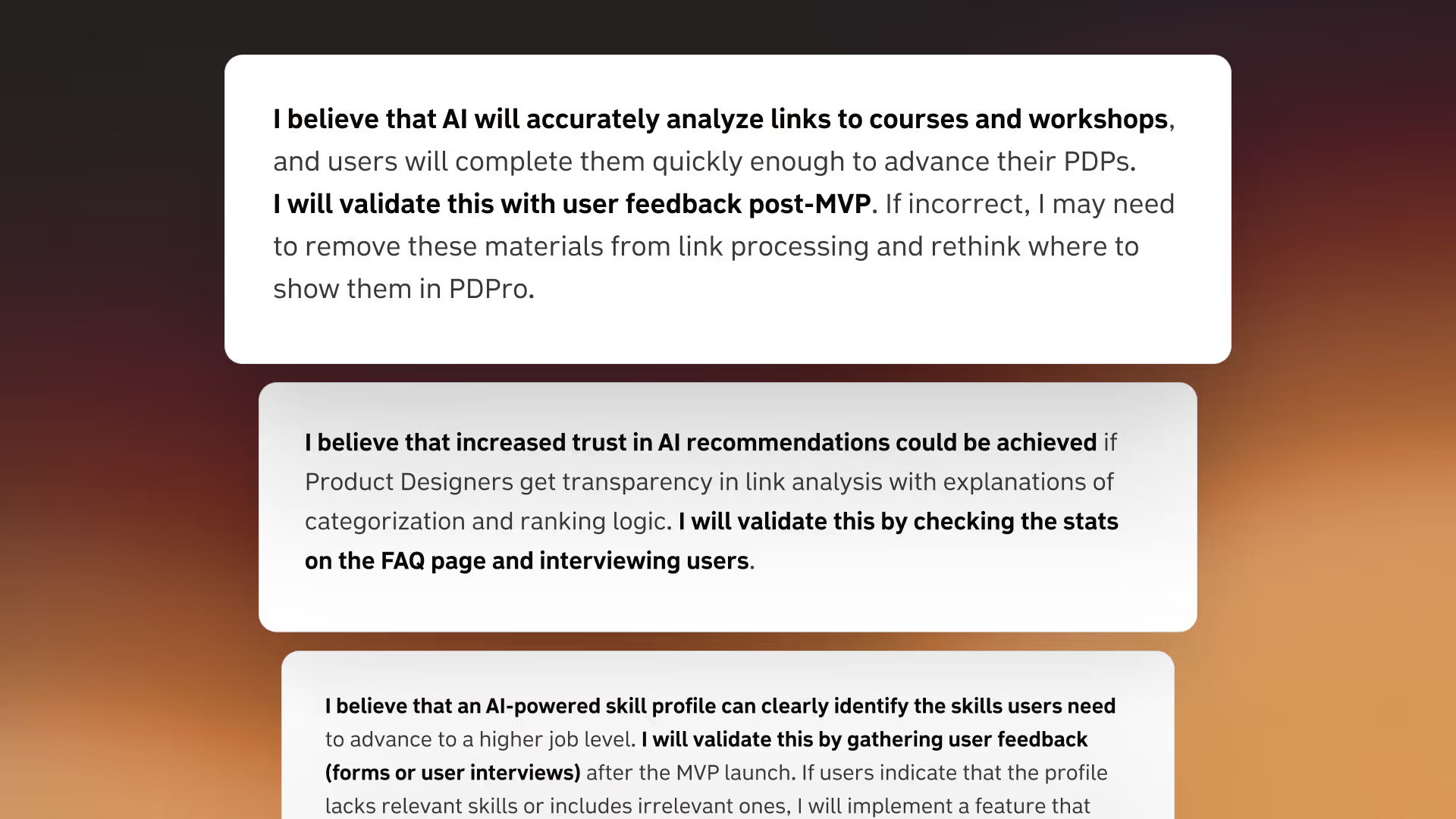

Most designers (myself included) aren’t big fans of writing them out. But honestly, it’s easier than it looks if you stick to a couple of simple formulas:

-

1. “I believe [assumption is true/false], and I can find out by [research method].”

-

2. “I will achieve [result] if [user group] gets [value] by using [functionality]. I can validate this through [research method].”

Where assumptions come from

An assumption can be any thought you have about your product that you’re not 100% sure about. If you like a structured approach (like I do), here are a few prompts from Jeff Gothelf’s book Lean UX:

User assumptions:

-

“My early users are…”

-

“They struggle with…"

Product assumptions:

-

“These problems can be solved with…”

-

“The most important features are…”

-

“The main value of my product is…”

-

“This is what it should look like…”

Business assumptions:

-

“I’ll get most of my users through…”

-

“I’ll make money by…”

-

“My main competitors are…”

-

“The biggest risk for my product is…”

-

“I can avoid this risk by…”

To make it less abstract, here’s a set of hypotheses I wrote while working on PDPro:

How to test hypotheses

When you’re building a product, new ideas pop up constantly (usually around 2 AM 😴). The question is: where do they go?

There are two main buckets:

-

assumptions/hypotheses list: If the idea feels important and could have a clear positive or negative impact on the product;

-

parking lot: A “holding area” for ideas that don’t solve the core user problem and would just add extra weight to your MVP.

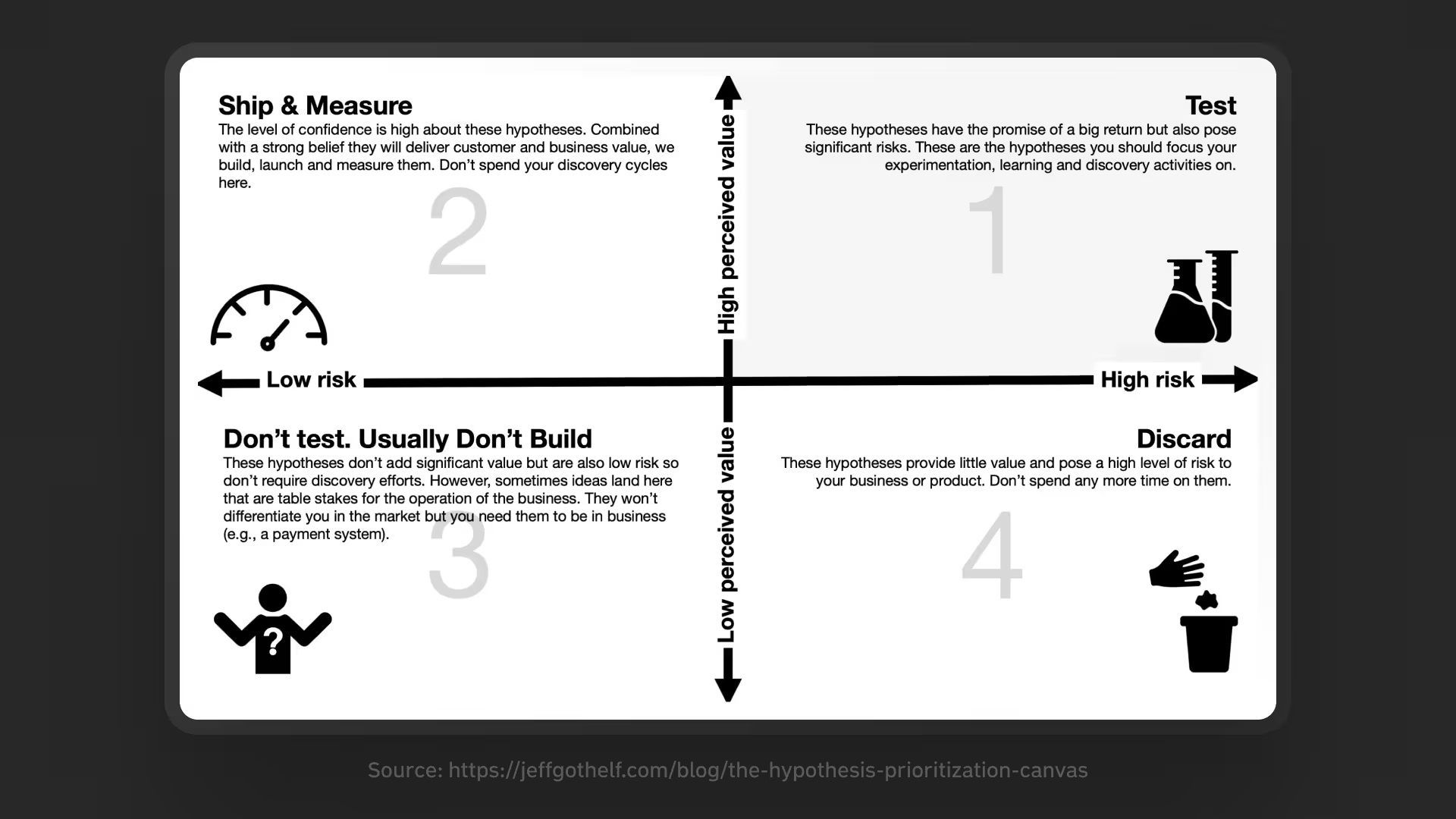

Trying to test everything at once is overwhelming, both for you and for respondents. That’s where a prioritization matrix comes in. It helps you decide what to explore first by mapping each hypothesis against two axes:

-

value: The potential benefit for users and the impact on your business goals;

-

risk: The possible downside for the product, including technical complexity.

Source: Jeff Gothelf

Keep in mind: hypotheses are never static. You’ll be adding and adjusting them all the time. Prioritization happens before each new research cycle, because that’s what determines what you’ll test next.

Move faster with AI

We live in a time where AI gets more powerful almost every week, sometimes every day. When I started building PDPro, AI tools were far less capable than they are now. But one approach I tried early on has stayed relevant even a year later.

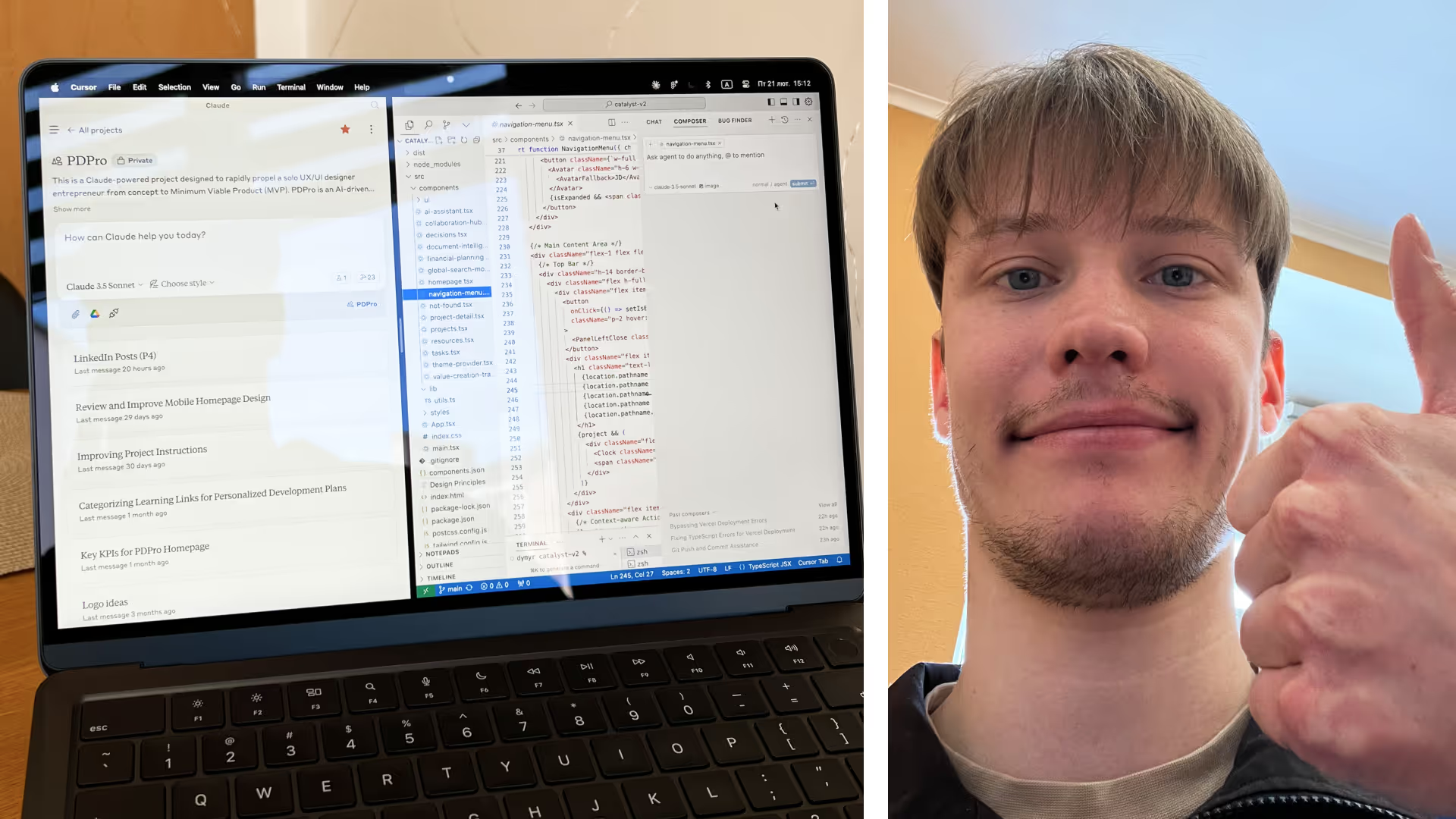

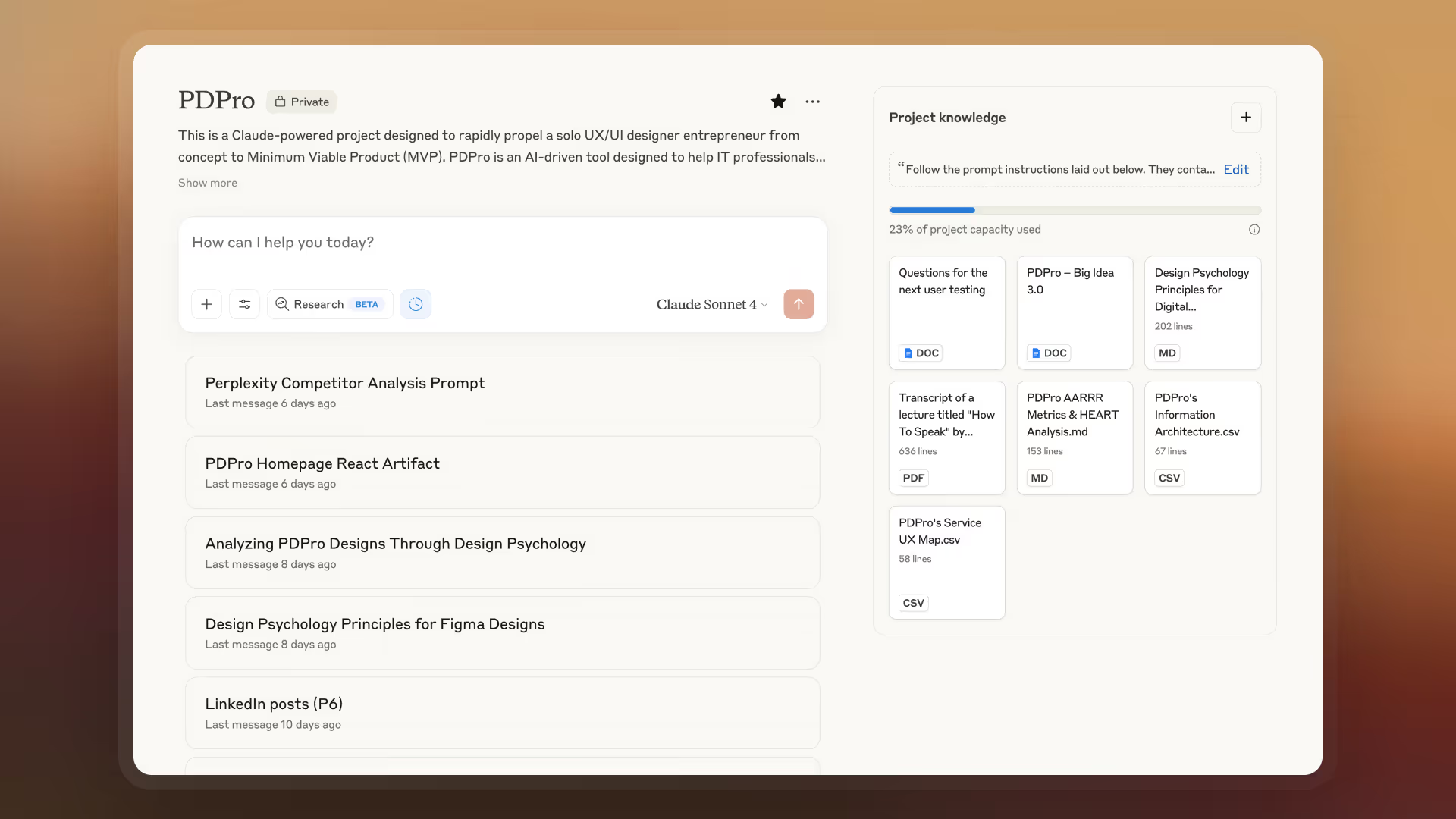

Claude Projects

This is a feature in Claude AI that lets you create a dedicated workspace for your project. Think of it as a super-smart teammate who remembers every little detail about your product and is available 24/7.

Other AI tools now offer similar functionality, but in my experience, Claude still delivers the best results when it comes to research and even development.

How to set it up

-

1. Get the subscription, it’s worth it (as of writing, it’s $20/month).

-

2. Create a new Project in Claude.

-

3. Upload your core docs (problem statement, personas, hypotheses, etc.) into Project Knowledge. These become your AI’s knowledge base.

-

4. Add instructions for how Claude should respond: tone of voice, what “role” it should take, and any rules it should follow.

-

5. Spin up as many chats inside the project as you need.

If you don’t yet feel confident creating all the product artifacts from your Big Idea doc on your own, just lean on AI as a collaborator. Write the way you normally would, ask questions, request advice, and co-create the documentation with Claude. Later, you can upload those drafts into Project Knowledge, too.

| 💡Important:

Project Knowledge is a living documentation hub that changes as your product evolves. The great part is that Claude lets you link Google Docs and Sheets alongside static files, so updates pull in automatically. No more re-uploading every time you tweak something. |

Strengths

When I needed to prepare a product artifact (say, a user testing script), I’d start a new chat and ask Claude for a draft. That gave me a solid starting point instead of a blank page. And if I later needed a similar script, I could just return to the same chat and build on it.

I go deeper into Claude’s (and other AI tools’) capabilities for product designers in a separate article, but here are the highlights:

-

keeps context across chats: Because everything lives in one project, you don’t have to repeat the same prompt or re-explain past conversations. Claude always refers back to your Project Knowledge, especially if you ask it to.

-

great for learning and insights: When set up well, 90% of the answers are spot on. And when Claude makes mistakes, it’s still valuable, as you get to learn new concepts explained simply, often with examples grounded in your own product.

-

fresh perspectives: We’re all biased in our own thinking. Sometimes it’s useful to hear an outside opinion, even if it’s from an AI. You can even tell Claude to role-play different personas and explain its reasoning in detail.

-

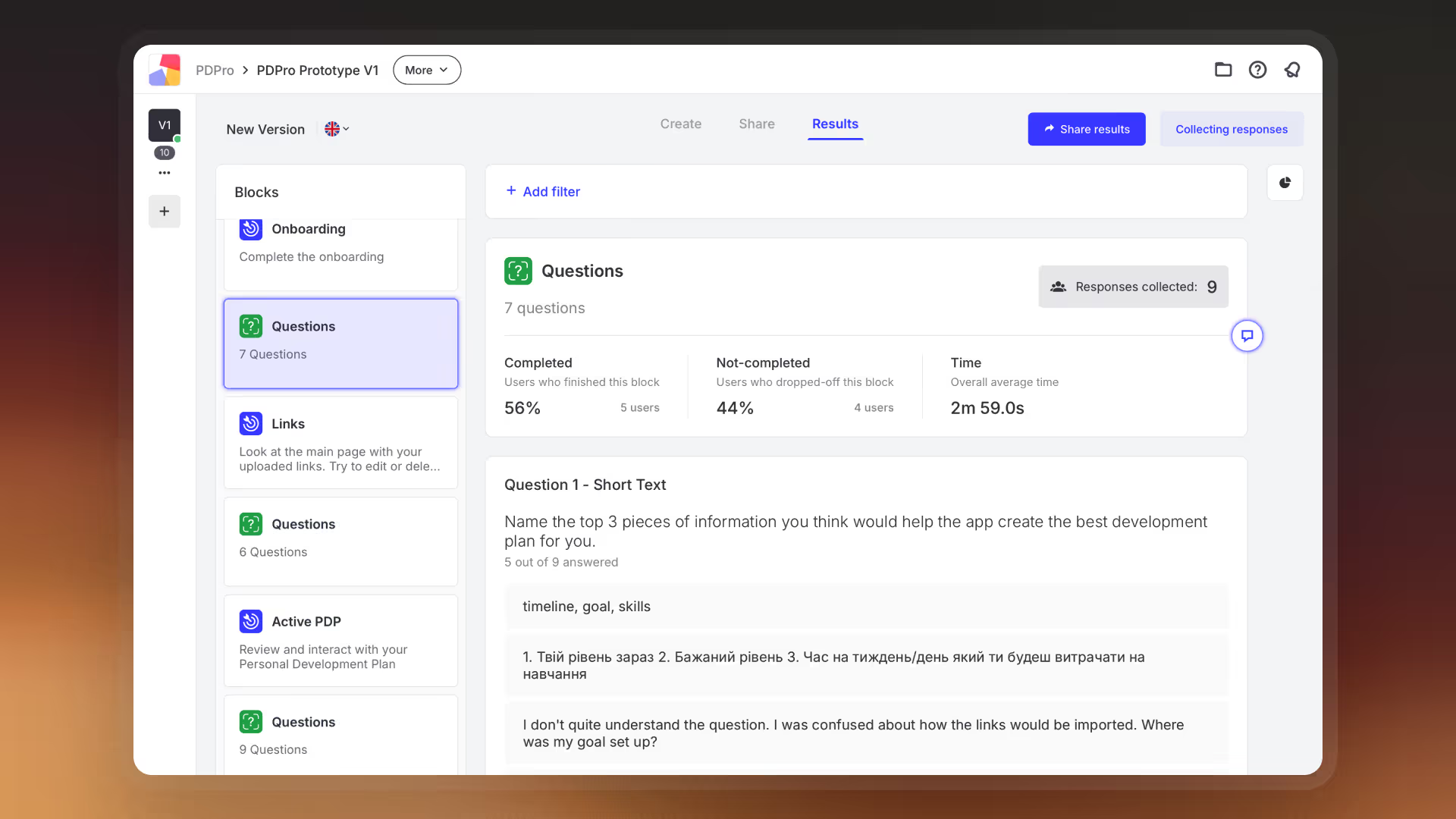

data analysis: This is where AI really shines. I used it to interpret survey results and usability testing feedback. What normally would take hours of manual analysis took just minutes.

Weaknesses

AI can be powerful, but it has limits and will never make final decisions for you. That’s always your responsibility. You need at least some experience in the domain you’re working in, so you can tell the difference between good advice and bad advice.

Also, keep in mind that the main goal of every AI assistant is to answer you even when it doesn’t know the right answer. That’s why it sometimes helps to explicitly tell the model: “If you don’t know, say ‘I don’t know.’”

And yes, the best results come when you work in English, which isn’t a bad thing, as it doubles as free language practice.

Prompt engineering

The quality of your outputs depends on the quality of your inputs. Set up your project carefully and give more specific prompts. For example, instead of just writing:

“Create a user survey.”

Say:

“I’d like you to create a user survey based on the knowledge from this project. Before you proceed, ask me any clarifying questions you have.”

This way, the AI itself will tell you what extra context it needs to generate the best result.

About two years ago, I read a few guides on prompt engineering and took a couple of courses. I even started drafting an article on the most powerful techniques, but AI moves so fast that the material was outdated before I finished. Still, one trick has stood the test of time. Whenever I’m not sure if my prompt is good enough, I use this template: