Magnus Hillestad is the CEO and co-founder of Sanity, a company with a gross revenue retention of 97%. Basically, nobody's leaving their product. How did they achieve that? By being intentional. This is Magnus’s favorite word. What he means by that is asking yourself what you are trying to solve as a startup and then focusing on that using frameworks like SCQA, Principles, V2Mom, and others.

This episode distills the essence of the learnings Magnus has undergone and the myriad of books he has read. If you want to be more intentional about your product, this one's for you.

Building a product vs building an organization

Ana Mudryk, Podcast Host and Head of PdM at Cieden: Magnus, you have tremendous experience in managing companies. You started 20 years ago with BCG and consulting companies, then you moved to sit on the board, and now you're managing a product company. What do you think are the traits of a successful company built on a product?

Magnus Hillestad, CEO and Co-Founder of Sanity: There are a lot of people who are really good at building a product but not at building a company, and they will struggle after some time. Conversely, many people excel at building companies but are not good at building products; they will struggle more immediately and definitely over time.

When building a product, if you can't quickly get people to find value in what you do and have to overly sell it, you're off to a difficult start. To me, building a company means creating one that could be worth billions of dollars and listed on the New York Stock Exchange, because that's the hardest thing you can do. Building a product can mean many things—it can be within a company or the company itself. Some people build companies with lower ambitions than ours, which is totally fine. You just need to be very aware of what you're trying to achieve. If you want to conquer the world, it's beneficial to have that goal in mind early on. Consider the shape of the company, what to prioritize, and how the business will play out.

I don't think you can ever substitute a good product. But the best product doesn't always win. If you focus too much on making the product good without understanding how to get it out to people, you're dead. Many great products were made at the wrong time or with the wrong execution.

There's a famous meme from Justin Kan, the founder of Twitch. In 2018, he wrote a line:

‘First-time founders are obsessed with product. Second-time founders are obsessed with distribution.’

Internally, I have a joke about third-time founders obsessing about the organization because, at the end of the day, it's the organization that builds the product.

PLG motion vs sales motion

Magnus: In the last quarter, we had 97% gross revenue retention at Sanity. That's because it's a really good product, and we sell it to people in the right use cases. Early on, we decided to follow a product-led growth motion, so we just put it out on the internet and saw who showed interest. We actually launched it while it was still an agency in November 2017. We were obsessed with who came on board and who was trying to use it. Whether you worked for Burger King or a church in Milwaukee, we didn't care. Of course, we understood that these two users have different revenue potentials over time, but their immediate reactions to using our software might not differ much. The value in their feedback may not be significantly different either. In fact, people who work for small businesses or a church in Milwaukee often have much less time and patience to decide whether the software is good or not, while enterprise users might be more inclined to push through and learn to use a big product over time.

Both types of users are extremely important, but if you don't have a very intentional approach to your go-to-market strategy, it becomes very hard to experiment once you start gaining some product-market fit. What patterns are you trying to establish in your company? When do you know whether to allocate more resources, pull back, or change your approach? Many people try a product-led growth motion but fail to make it work and then switch to a sales motion, which can be easier to kick off, especially in the early days when the co-founders are selling.

There's some magic pixie dust in a co-founder trying to sell a product they've been deeply involved with. Of course, you can sell it. Achieving a couple of million dollars in ARR on the back of a co-founder is less impressive than taking people off the street, who might have some industry knowledge but not about your product, and training them to sell it effectively. Ensuring that customers afterward say, "this is amazing," means you've successfully built a company on the back of a good product.

The sales equation

Magnus: Our VP of Sales, CK, always talks about the sales equation. I really like this way of thinking—seeing the company as an equation with a bunch of unknowns. What you’re trying to do is figure out patterns and facts about these unknowns. I often say internally, “Don’t try to optimize it. You can’t optimize an equation while you’re still figuring out what the heck that equation is.” When building the company, you need to understand what’s actually happening and how things are working.

For instance, when we talk about the cost of our sales-qualified opportunities, I don’t really care about the cost until we have a repeatable pattern that we need to learn from. Otherwise, you’re just optimizing for the sake of it. I think a lot of people, maybe product people, try to optimize too early. But if you’re good at building your company, you won’t optimize too soon. A startup is really about momentum, not optimization. There’s so much opportunity out there, especially if you’re targeting a decent-sized market and aiming to go big. You shouldn’t focus too much on immediate details. People often say, “There’s money left on the table with this customer.” Who cares? There are millions of customers out there. Leaving 10% of the money on the table isn’t the point.

Ana: Actually, Elon Musk suggested a good approach to optimization: start by deleting unnecessary steps. First, audit what you have, then eliminate steps, optimize the remaining ones, and finally automate. I think that's the right way to set up processes—understand what you need to do first, and then optimize. It’s also a good way to think about scalability. There are so many parts to a business, from hiring to building products, and managing everything on the backend. It’s crucial not to over-invest in one area, like sales, without keeping up with other parts of the business, or to push too fast with product development without aligning with sales. Orchestrating all aspects of the business while keeping an eye on every part and progressing step by step is key.

Frameworks for managing a product

Ana: Do you have any framework that you use in Sanity to decide what is important? When Jeff Bezos started Amazon, he invented a framework for minimizing regrets. So, what’s your framework?

Magnus: Good question. I don't think I have a great framework but I combine some: the one-minute, one-day, or one-week decision framework, the principles by Ray Dalio, SCQA, Let Fires Burn, and The V2Mom framework.

The one-minute, one-day, or one-week decision framework

The one-minute, one-day, or one-week decision framework is a useful way of thinking. In a startup or any company, it's often better to make a quick decision and adjust later. I 100 % subscribe to that.

However, it's crucial to understand what you're trying to decide. This framework promotes intentionality—one of my favorite concepts. Be intentional and strategic. Strategy, to me, is about reflecting on what you aim to achieve, whether you're a developer, salesperson, or CEO. Ask yourself if the decision needs deep consideration and if it's a one-minute, one-day, or one-week decision.

One of my first considerations is whether a decision is a no-regret one. Is it a revolving door or a two-way door? Can I change my choice if it's wrong? It's like answering a 50-50 question—you look smart half the time. If a decision is reversible, make it.

I tell my colleagues to make decisions without fear of mistakes. We must address, discuss, and learn from our mistakes, even if it's uncomfortable. Embracing this discomfort is vital for an organization. Trust is a core value, but it must come with accountability and the willingness to learn from errors.

Additionally, the first question when solving a problem or making a decision should be: Who should make this decision? Not what the answer is. Often, people jump to find answers instead of identifying the best person to decide. So who should own the decision? I think it's tremendously important.

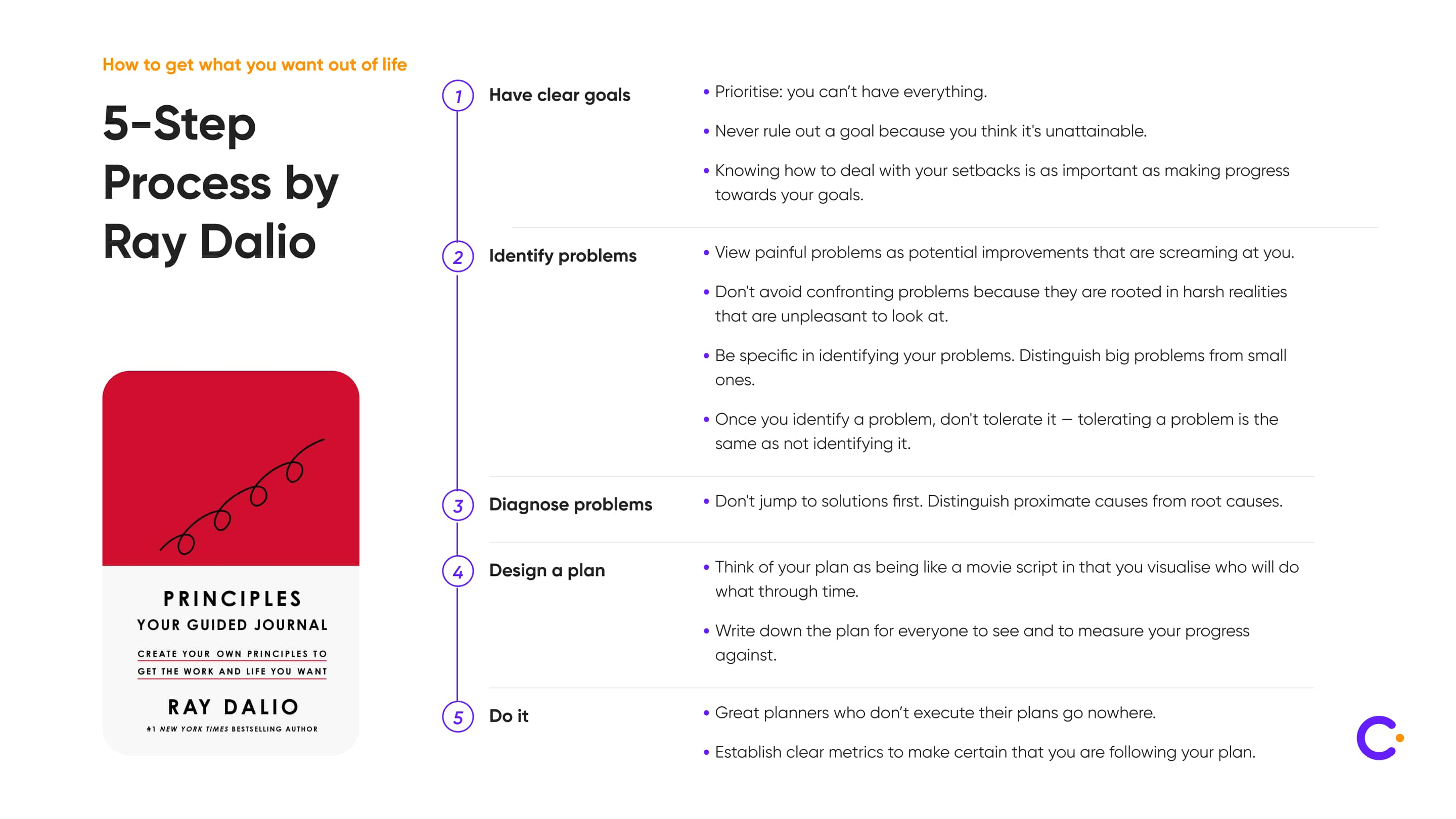

The Principles framework by Ray Dalio

I also really love Ray Dalio's work. He's the hedge fund founder who wrote "Principles." Ray Dalio talks about writing down all his decisions, their outcomes, and the principles behind them. This approach has helped me, although I don't use it systematically. He says that most of your decisions come down to a pattern of ten main types. When faced with a decision, identify which of these ten it is, determine the best methodology to find the answer, and review your track record with that type of decision. It's a very structured approach.

Ray Dalio is a fascinating and unconventional person, but he's been extremely successful. If you read "Principles," you'll be amazed by his unique practices at Bridgewater, which have led to massive success. I also appreciate the idea of determining who should make a decision, a concept from "Trillion Dollar Coach," a book by Eric Schmidt about Bill Campbell, a famous coach in Silicon Valley.

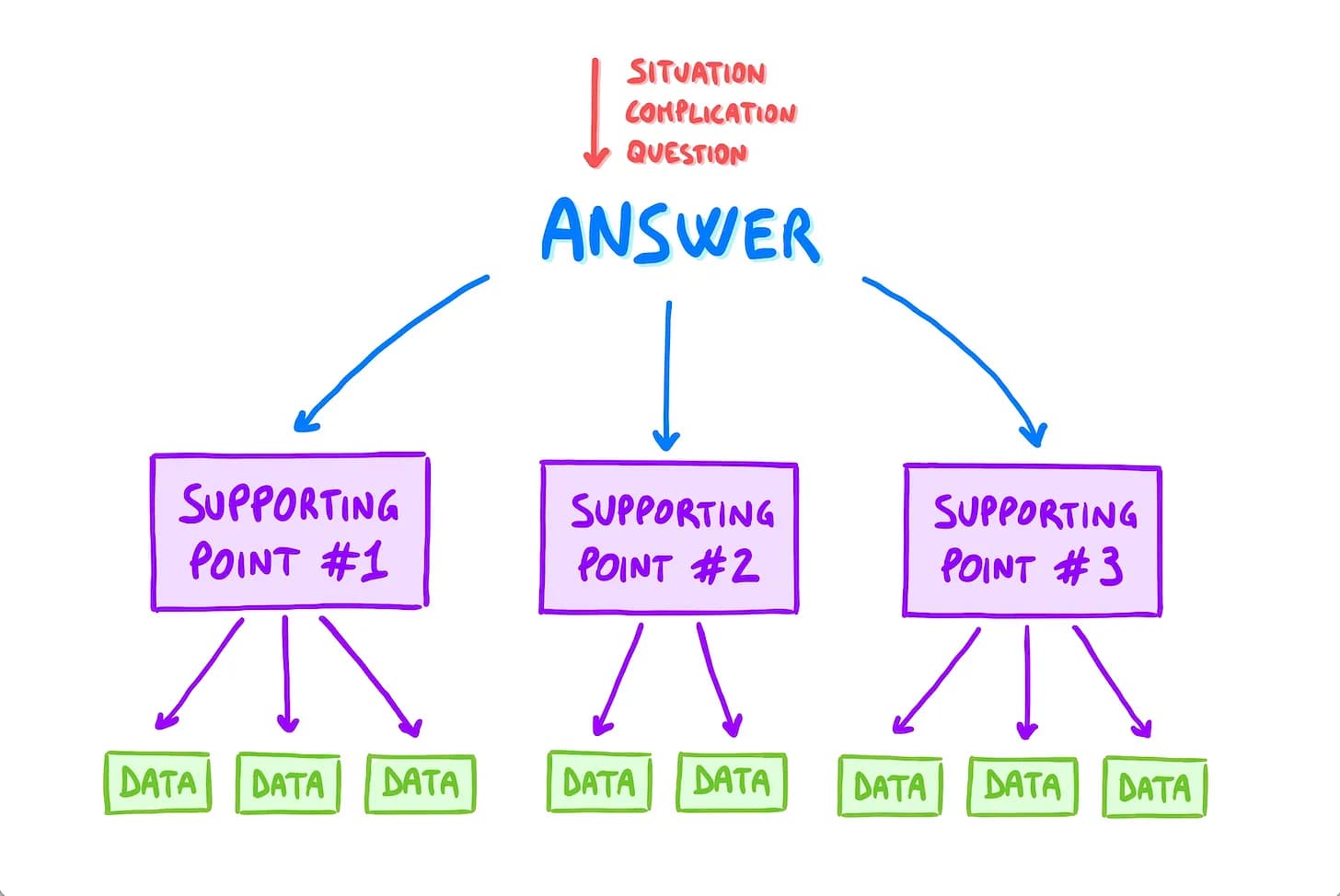

The SCQA framework

The framework we use most frequently and recommend to others is the SCQA framework: Situation, Complication, Question, and Answer. Created by Barbara Minto, a pioneering female consultant at McKinsey and one of the first women at Harvard Business School, this method is detailed in her book, Pyramid Principle. I learned about SCQA from Michael Dearing, a current investor and former eBay executive, during my first meetup in the Bay Area after moving from Norway five years ago. Dearing's presentation on executive communication, available on Heavybit, simplifies Minto's principles.

The SCQA framework helps organize thoughts and clarify intentions. The "Situation" covers the undisputed facts everyone agrees on. The "Complication" identifies the core problem, which is crucial to address since agreement on the problem is necessary before finding a solution. The "Question" asks what should be done about the complication. The "Answer" can either propose a solution or indicate a need for further discussion. Following Minto's structured approach to argumentation helps build strong supporting arguments and facts.

Source: Luca Rossi

Let Fires Burn

One of our core values is "Let Fires Burn." You need to ask yourself: Do you really have to decide on every issue? Is it a blocker to moving forward or creating clarity? If not, why spend time on it? Startups face many fires, and with more people, these fires multiply.

Often, startups think that the number of employees is a good KPI for success, adding people as much as possible. We've done this too, sometimes with mixed success. We've had to reverse decisions because we weren't intentional about what problems we were solving and how. The number of employees is not a true measure of success—it's merely an easy way to gauge size and says nothing about effectiveness.

For instance, at EQT Partners, when we hired internal tax lawyers, our tax reporting increased significantly. This focus wasn't appropriate for our company's size at the time. The same happens in any company: hire someone for a specific task, and that task will suddenly become a major focus.

Ana: If you have a plumber, everything becomes a nail.

Magnus: Exactly. When you hire someone to solve a problem, they'll focus all their efforts on it. No one says, "This problem doesn't require my full attention, so I'll look at something else." Although some exceptional people do that, and they're the A-plus players you want on your team. It makes their behavior predictable, but also valuable.

The V2Mom framework

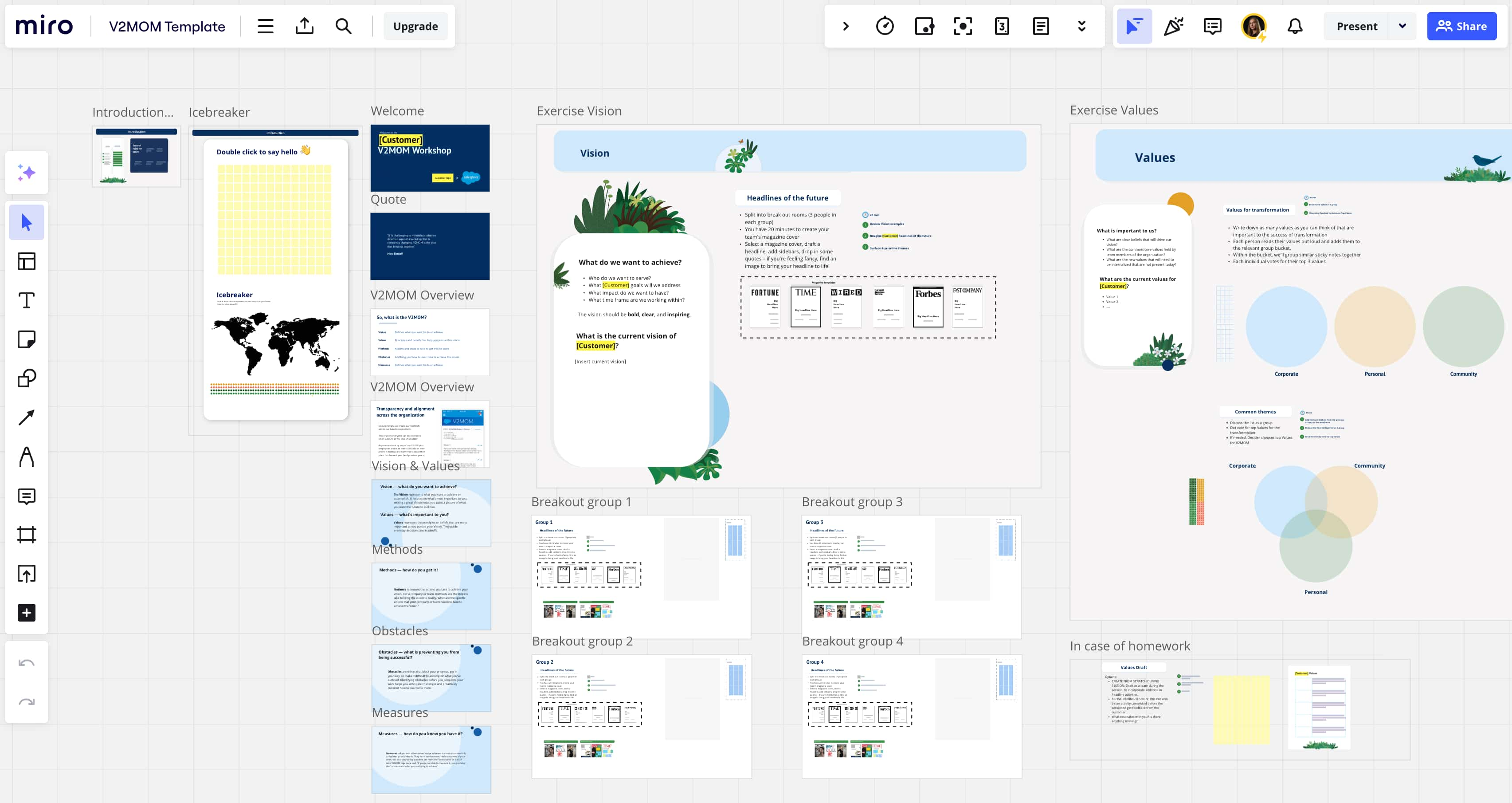

You were asking about frameworks, and I didn't mention V2MOM, an alignment framework we use, created by Salesforce. V2MOM stands for Values, Vision, Methods, Obstacles, and Measures. It's similar to OKRs, which were invented by Intel and popularized by Google. OKRs are very numbers-driven and can sometimes feel like tasks. The effectiveness of any system depends on how you apply it.

A good friend, the former CEO of Heroku, introduced me to V2MOM. It’s a bit more verbose and focuses on vision. We use it to align our goals by identifying what we aim to achieve and the methods to get there. Each method has associated obstacles and measures, with various teams responsible for these. This year, we have five main goals, though the number varies. Everyone in the company knows these goals and focuses on them.

You can find a free V2Mom template here.

A startup isn’t limited by opportunities but by its execution and focus on the right things. This is crucial for making significant improvements. We discuss this extensively during our quarterly business reviews (QBRs) with core management. Recently, we had one in Hoffman Bay, where we spent a couple of days together, went for morning walks, and reviewed our V2MOM progress. This approach has been successful for us.

For those looking for tips, I recommend the book "Traction," which discusses building an operating system for your company. While I haven't tried their exact methods, it raises awareness and encourages intentionality in running a company. Ultimately, having a framework helps you be more deliberate in building and growing your company, aiming for goals that are 10X what you have today.

AI in the CMS industry

Ana: So, the last question I’d like to wrap up with is about AI. How do you see AI impacting the CMS market and industry overall? Currently, there are technologies and machine learning/AI algorithms that allow the creation of content on the go. You can create personalized experiences, websites, and different content. Do you feel threatened by AI, or will it be more of a supplementary feature for your business and product? How do you see this industry evolving in a couple of years?

Magnus: Yeah, that's a good question. It's definitely an opportunity, not a threat. AI is going to be everywhere and enhance the way we work in many forms. The CMS industry has historically been extremely web-centric. For us, content is really about having a platform that can serve all your different needs, whether it’s an app, a website, a web app, or an internal app. To make content strategic, you need to control and understand it, work collaboratively with machines and people, and distribute it as needed. This is how we set out to build Sanity—focused on unstructured content.

Initially, it was hard to derive structured content from unstructured data, but that has changed. However, large organizations still need frameworks for communication and reusability. AI will amplify this need. We've already seen the consumerization of content, leading to a lot of noise. Imagine the noise we’ll now get with AI. I remember a guy on LinkedIn got criticized for showing a bot that answered LinkedIn messages automatically—no one wants that kind of noise. Instead, we need to harness LLMs to assist effectively.

We released AI assist a year ago and, in May, launched Sanity Create—a writing assistant that enhances creativity using AI. There's still a long way to go, but larger organizations need controlled and understood communication, so AI can't be left unchecked. The content platform will become even more crucial. We've moved from isolated systems to a more connected world where the best companies deploy technology and developers at scale. Developers won't go anywhere. They'll come more efficiently. They would probably change the way of working. Like CMSs won't go anywhere, developers will start engineering platforms instead of marketing platforms.

Ana: Yeah. Magnus, it was an amazing conversation. There are so many things that I think I will use in my projects right now about decision-making. And I have one thing where I would use this framework that you mentioned.

Magnus: I have a bonus tip for you. This is something I say a lot: There’s no such thing as an unprioritized list. Every list you make has a subconscious prioritization. You need to be intentional about it. So, there’s no point in having bullet lists—might as well give them numbers.

Ana: So true! Thank you so much.

Magnus: Thank you. Nice chatting, bye.