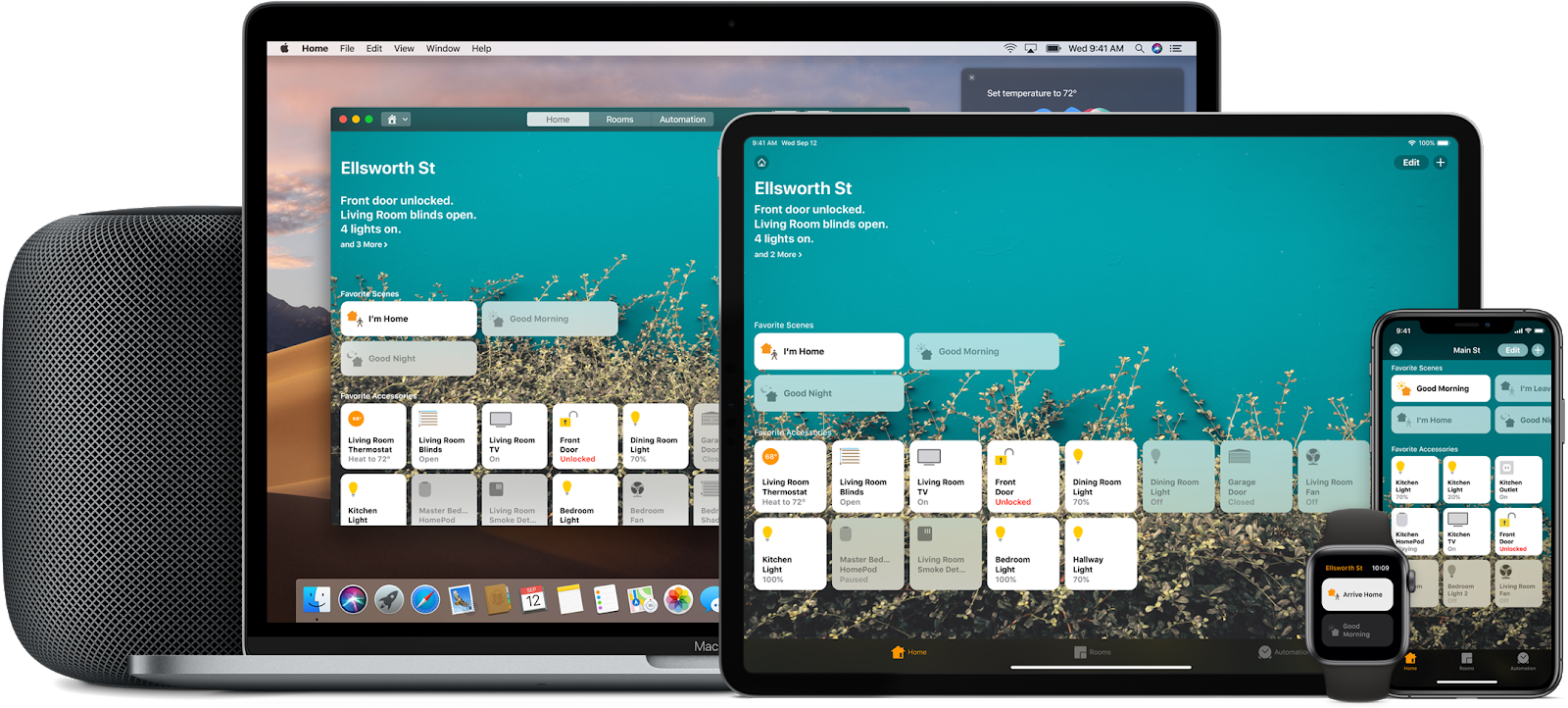

In an ever-evolving world, adaptiveness to change is key for your product not only to survive but flourish. That's why product owners should maximize the agility and adaptiveness of their product development processes.

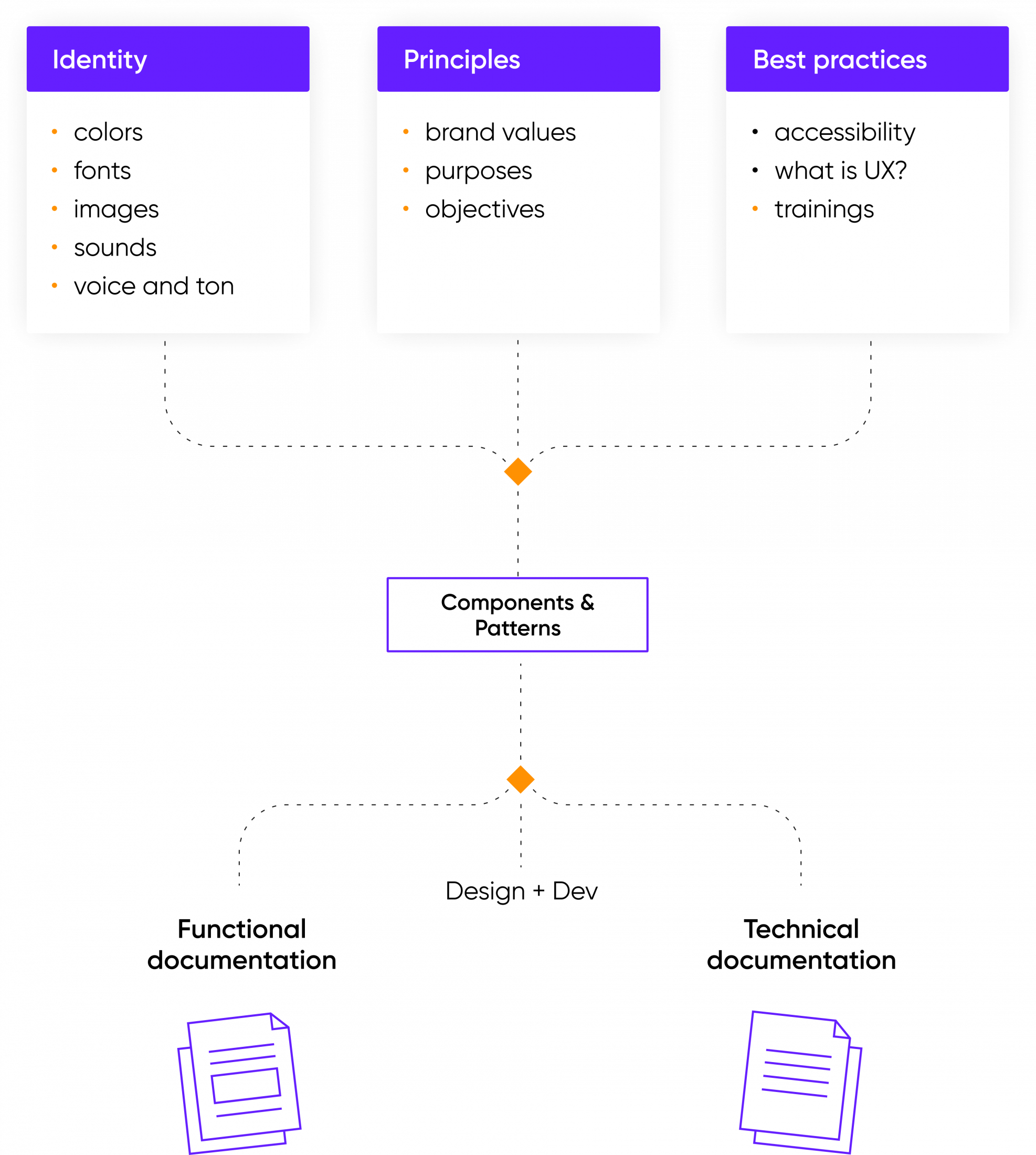

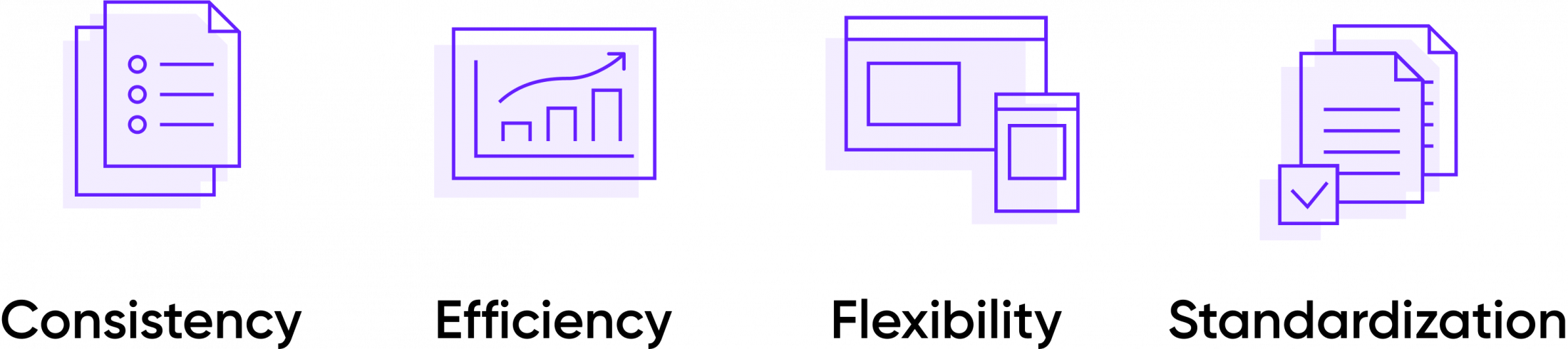

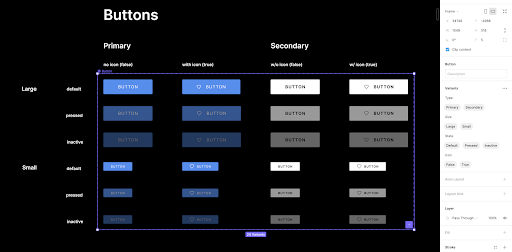

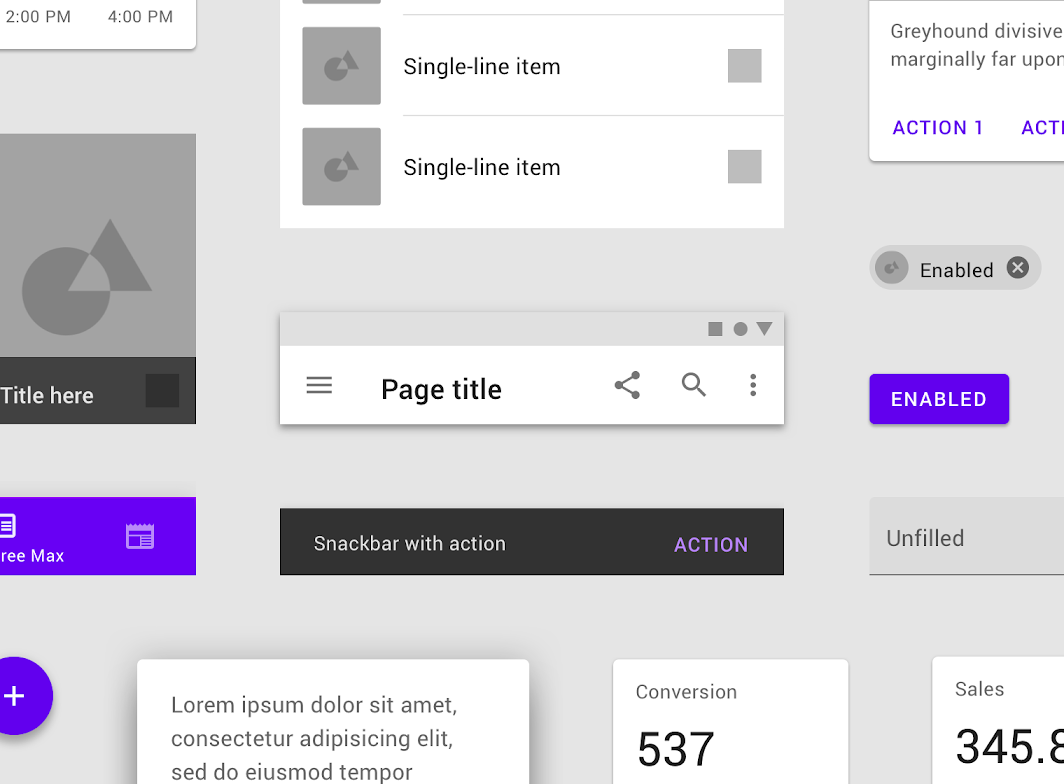

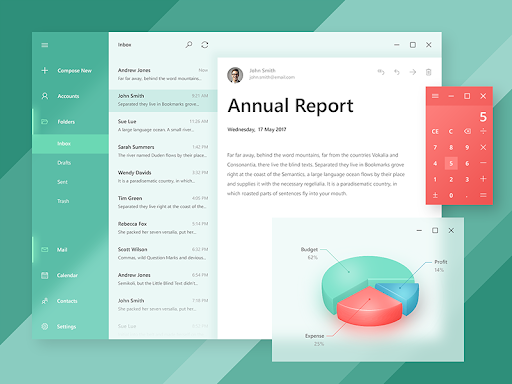

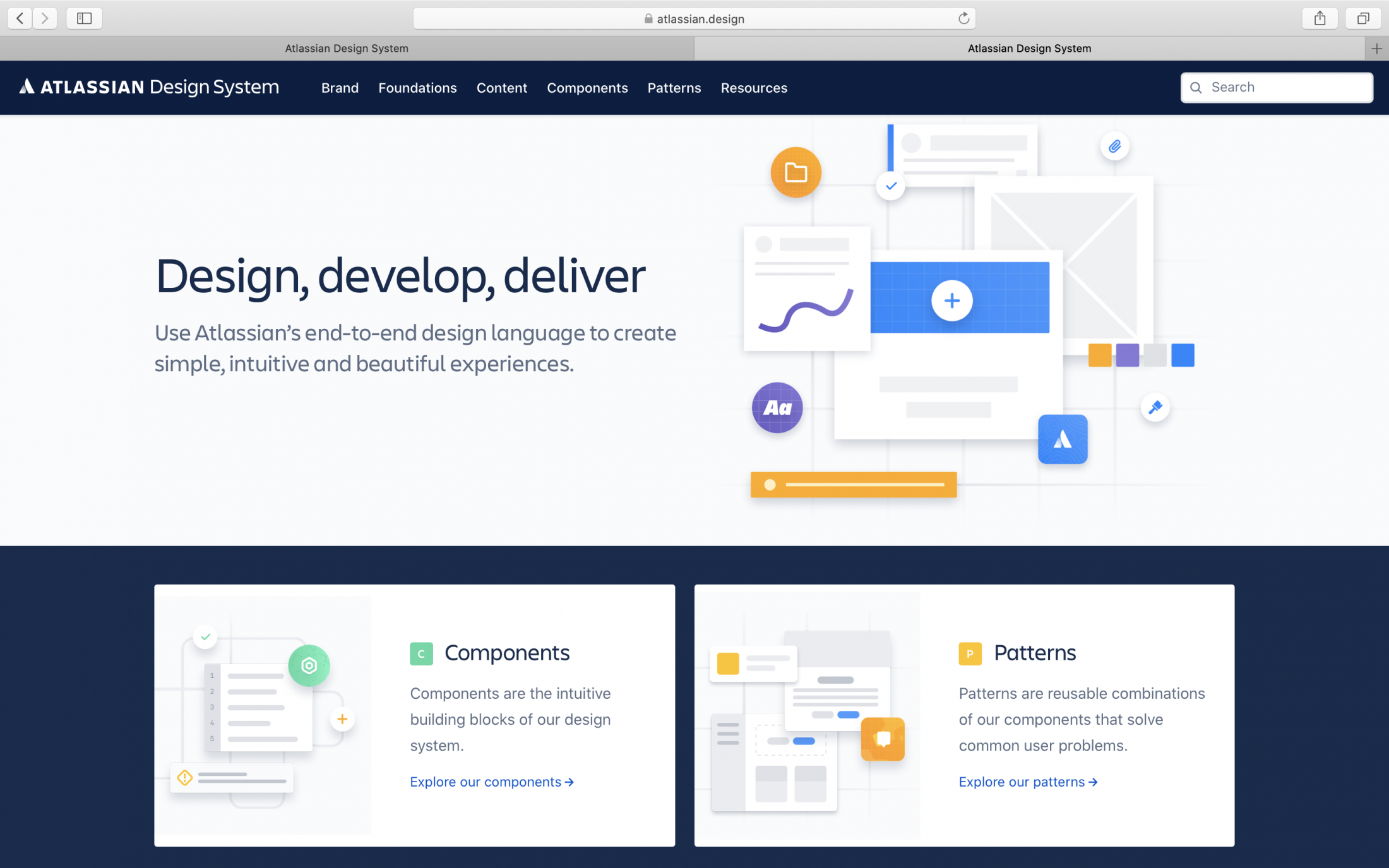

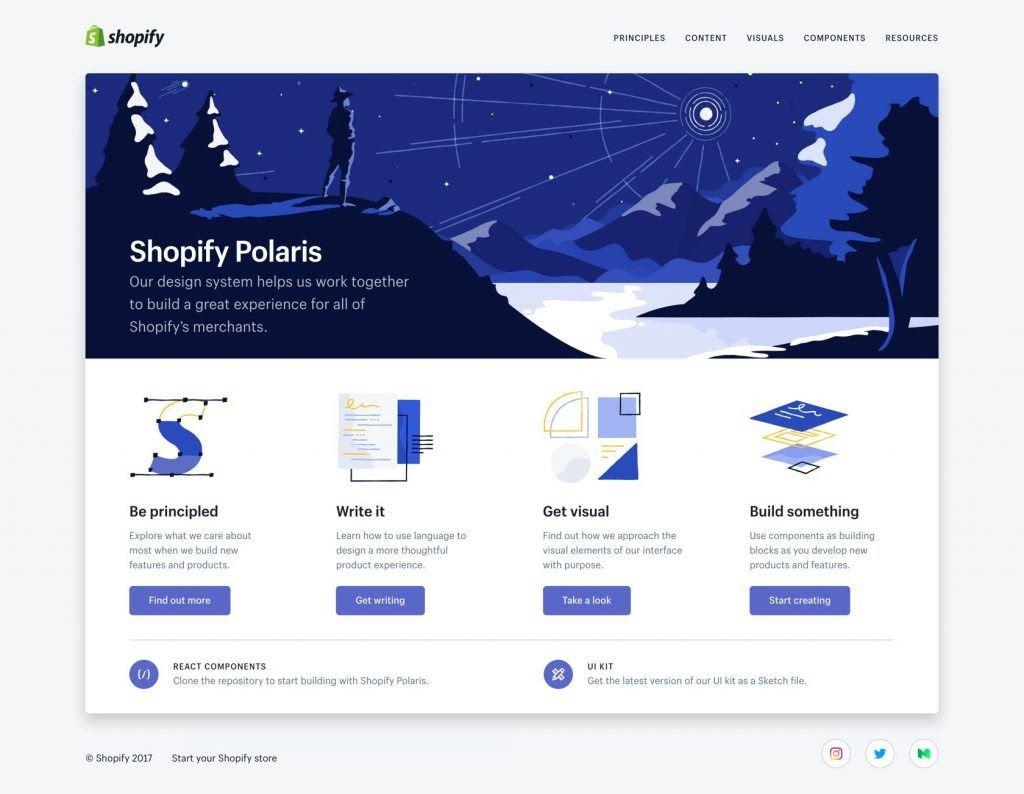

One of the most potent ways to save time and money is to standardize and reuse the elements you've already built. In fact, such formalization practice is commonplace and often indispensable in the professional UI/UX design realm. This is what this article is about: saving time, money and effort, while also maximizing the efficiency of your product team. In other words, this article is about design systems.